One of the early discoveries of the differences between prop-pulled and jet-propelled airplanes was that the latter benefited a great deal from the availability of speed brakes. When the pilot pulled the throttle to idle on the former, the propeller pitch changed rapidly to maintain rpm and the drag increased significantly; there was no need for speed brakes (there were exceptions: dive bombers needed dive brakes to keep the speed within reason in a near-vertical dive; the Grumman F8F Bearcat had small dive-recovery flaps under the wing to more quickly pull out of high-speed dives). Jet planes slowed down with the throttle reduction but far more gradually.

The speed brake design specification was a reduction from maximum speed to a specific slower speed within a given number of seconds. Avoiding much of a pitch change with extension or retraction and minimal buffet when extended was also desired.

The U.S. Navy's first jet, the McDonnell FD-1 (subsequently FH-1) Phantom had speed brakes similar to the spoilers necessary on gliders to allow for the adjustment of the glide angle on final approach. They both increased drag and to some extent, reduced lift. They extended up and down out of the wing on a parallelogram mechanism.

North American initially fitted its FJ-1 with a similar system.

However, after one side extended and the other didn't during a flight test, causing an uncommanded roll and the pilot some concern, North American substituted speed brakes scabbed onto each side of the aft fuselage.

Note that the actuator is located in a well but the speed brake itself simply closes onto the exterior skin of the fuselage.

Vought didn't initially provide its first jet, the F6U Pirate, with speed brakes.

One was quickly added to each side of the aft fuselage:

Grumman provided two speed brakes on the belly of the F9F Panther fuselage just aft of the nose wheel well. The location was retained through the Cougar; however, the F9F-9/F11F Tiger was designed with three speed brakes, one under the nose and two under the main landing gear wheel wells.

Douglas initially configured its F3D Skyknight with three speed brakes on the aft fuselage, possibly to insure the ability of the all-weather fighter to slow down as quickly as possible behind a bogey being intercepted so as not to overrun it or worse, run into it.

![]()

Photo via Paul Bless

However, the lower dive brake was deleted for production.

McDonnell retained the FD/FH wing-mounted speed brakes through the F2H-3/4 Banshees.

On the F3H Demon, however, the speed brakes were relocated to the more common position, either side of the aft fuselage, probably dictated by the different airflow on a swept wing.

Speed reduction was considered particularly necessary when Vought began testing the F7U-1 Cutlass that was capable of breaking the sound barrier in a dive. The problem was that if its single hydraulic system failed for any reason, the control loads became very heavy, increasing with speed. As a result, in addition to the split speed brakes on the inboard trailing edge of the wing, another pair of speed brakes was added under the engine inlets to slow the Cutlass down as quickly as possible so the pilot could regain control.

The extra pair of speed brakes was unnecessary on the F7U-3 since it had a fail-operate flight control system.

Sometimes the aft fuselage lacked a suitable surface for the location of speed brakes. The Douglas F4D Skyray had four small ones, mounted above and below the fillet inboard of the wing.

McDonnell placed the F4H's speed brakes on the bottom of the wing, sandwiched in between the main landing gear wheel well, the trailing edge flap, and the aft Sparrows:

Sometimes it took the engineers more than one attempt at locating the speed brakes. For example, this was the F8U mock up (note that the cannons are located directly under the forward fuselage);

On second thought, they made it a single panel on the belly aft of the nose wheel well and moved the cannons to the side of the forward fuselage.

While this meant that the F8U couldn't be landed with the speed brake extended, the primary reason for that was to add drag on approach so the engine response from the higher thrust required was quicker. Raising the wing for landing provided more than enough drag for that purpose.

The General Dynamics F-111 speed brake doubled as the forward main landing gear door:

![]()

The pilot had to bear in mind the increase in drag when the gear was retracted.

On the F-14, Grumman located the speed brakes on the upper and lower surface of the aft fuselage between the engine nacelles, a single brake above and two below—also see http://www.anft.net/f-14/f14-detail-speedbrake.htm

On the F-18A/B/C/D, McDonnell utilized a single speed brake on the top of the aft fuselage that doubled as a billboard.

The Navy determined that some of its jet attack airplanes needed more (and in one case less) speed brake than originally provided.

The North American FJ-4 was repurposed to be a backup to the Douglas A4D. Among other detail changes for the mission, an extra pair of speed brakes was added under the aft fuselage.

The Navy also decided that the original pair of A-6 speed brakes mounted aft of the engine were inadequate so Grumman added a pair of split panels to the trailing edge of the wing tip.

Ironically, it was subsequently decided after some service use that the fuselage-mounted brakes were a problem and the wing-tip ones were adequate, so the former were deleted in production and made inoperable on existing A-6s.

The Vought A-7, originally dubbed the Attack Crusader, was provided with a somewhat bigger speed brake for its strike mission capability;

Although it did not have the raised wing for added drag on approach and extended even farther down than the F8U's, the low-bypass fan engine was presumably deemed to be responsive enough at approach thrust, not to mention the drag of the multiple pylons on the wing.

The North American A3J Vigilante prototypes were built with an enormous speed brake under the fuselage.

However, the Navy decided to delete it for production. The speed brake function was instead provided by the lateral control system, which consisted of deflectors and spoilers on the wings. Instead of them extending asymmetrically for roll control, they all extended at the same time for speed reduction.

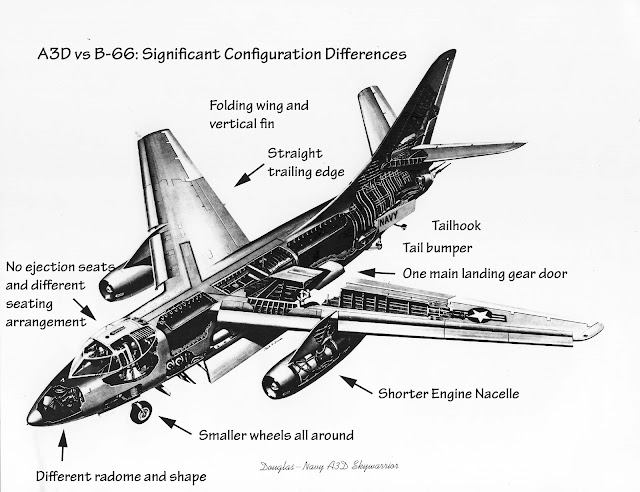

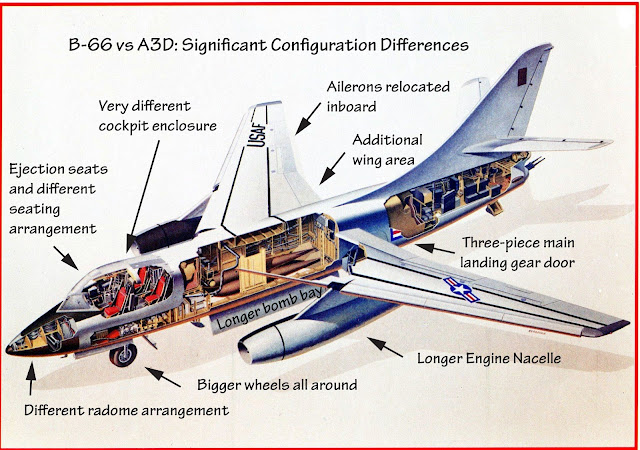

The Douglas A3D Skywarrior was also utilized for "dive" bombing, but what looks like a speed brake in front of the bomb bay was actually a spoiler that extended along with the bomb bay doors to eliminate the recirculation of air inside the bomb bay. Otherwise, the bombs would rattle around in the bomb bay after being released instead of dropping out.

The ultimate in speed brakes, however, is similar to the A3J/RA-5C's in that there is no dedicated speed brake per se, but much more effective. The F-18E/F's fly-by-wire flight control system permits speed control without speed brakes by utilizing the existing flight control surfaces, flaps, and the leading edge extension spoilers to add drag when desired. (Note that the flight control system is also programmed to toe-in both rudders for takeoff and approach for lower nose wheel liftoff speed and improved longitudinal stability respectively.)

The leading edge extension (LEX) spoiler had been added to disrupt the LEX-generated vortex that allows for controlled flight at very high angles of attack. When the pilot adds sufficient forward stick at a high angle of attack, the spoilers extend to disrupt the vortex, which results in a faster nose-down response.